Ghassan Salhab

2021أشباح بيروت

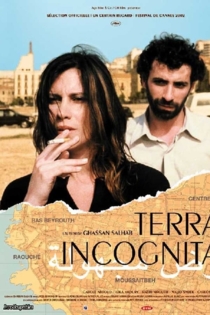

Ghassan Salhab

Aouni Kawas, Darina Al Joundi

Late in the 1980s it seems like the Lebanese conflict will never end. Khalil returns to Beirut after many years. Ten years earlier, during a battle, he took advantage of the confusion and pretended he was dead.

Beirut Phantom

Le dernier homme

Ghassan Salhab

Carlos Chahine, Faek Homaissi

Each morning Beirut awakens to a new murder seemingly committed by a serial killer, with victims found emptied of their blood. At the same time a doctor, Khalil, begins to experience strange symptoms that destabilise him and transform his life. A connection slowly emerges that seems to link Khalil to these victims. Salhab’s body of films have come to narrate the state of Lebanon – and Beirut in particular – during and after the civil war, and this film is no exception.

The Last Man

The Mountain

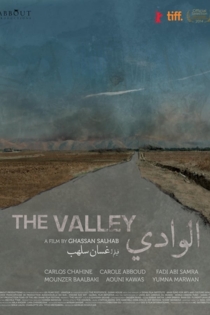

Ghassan Salhab

Fadi Abi Samra

Night falls over Beirut. Fadi, a forty year old, packs his luggage and sets out to the airport with his friend driving him. He is supposed to leave for a month, but instead of going up the plane, he heads to the arrivals section and rents a car. He takes the highway heading North then continues on a mountainous route. Far from anyone, on a deserted highway, a deviation forces him to quit the main road. A distinct sound coming from far is heard; the sound of a car honk. Fadi gets closer and closer to the sound and sees a wrecked car crashed in a tree alongside the road. A couple lay still inside.

The Mountain

Heber Sini

Ghassan Salhab

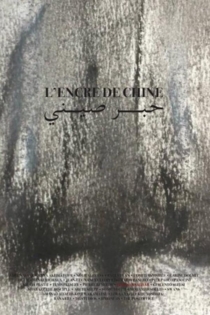

In Chinese Ink, composed from a series of shots taken with an iPhone, Salhab expands questions of location and the act of filmmaking itself. Some images were captured in the moment ‘without quite knowing why’, and others were filmed at an earlier time ‘with no apparent motive’ or as a result of specific circumstances. Salhab jotted down notes all along, excerpts from books he read or reread, sounds he recorded and preserved. He approached this film essay as a work in progress with no preconceived structure; instead, he let the work gradually reveal itself. All at once, in terms of ‘place’ and his relationship to ‘here’, with all its entanglements, it became clear to him that he needed to invoke the ‘elsewhere’, to start with the first place, his childhood in Senegal, and ‘retrace’ certain steps: his connection to armed struggles, the Palestinian cause, the present moment.

Chinese Ink

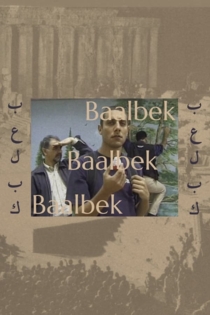

Al Naher

Ghassan Salhab

Ali Suliman, Yumna Marwan

It's autumn. A man and a woman are about to leave a restaurant situated in the heart of the Lebanese mountains. They are suprised by fighter planes screaming past at low altitude. In the distance, war seems to be breaking out once more. Losing sight of the woman, the man starts looking for her. He finds her on the other side of the mountain. Together they sink deeper into nature, which becomes increasingly spectral, just like the slender thread that ties them to each other.

The River

Posthume

Ghassan Salhab

Ghassan Salhab, Rabih Mroué

Following on from the 2006 Israeli aggression on Lebanon, the filmmaker tries to film the destruction of Beirut. We witness a city deserted by life, and ghostly characters who, featured in his earlier films, talk about living through such a war.

Posthumous

An Open Rose

Ghassan Salhab

Rosa Luxemburg’s letters from prison form the backbone of Ghassan Salhab’s essayistic collage. Luxemburgs’s lyrical descriptions of nature bear witness to a joie de vivre undimmed by the political situation of the time and are not seen, but rather heard – in both German and Arabic. In connection with images of a wintry Berlin, a polyphony of different overlapping visual and acoustic layers is produced.

An Open Rose