Michel Nedjar

1947 (78 лет)In 1960, he became aware of the magnitude of the Holocaust. At the age of fourteen, he enrolled in a vocational school to become a tailor and sells jeans with his flea grandfather from Saint-Ouen and accompanies his grandmother to the scrap fair; she makes him share his love for Shmattès (the worn cloth) that she picks up and stacks. In the spring of 1967, he left for military service. With tuberculosis and declared disabled in 1968, he spent a few months in a school of fashion stylist. He is upset by the vision of 'Night and Fog' by Alain Resnais, echoing his own disappearances in his family.

In the years 1970-1975, he left with Teo Hernandez. His travels take him to Morocco, Asia Minor, Europe and Mexico. He discovers cultures rich in symbolic expressions. He begins to take an interest in the funeral art and the dolls whose magic function fascinates him. Returning to Paris in 1976, he began making his first dolls called "Chairdâmes" with rags that he gleaned in the neighborhood of the Goutte d'Or, then made dolls dyed. In 1978, a period of depression transformed his style: his dolls look like gargoyles and terrifying totems, they are sometimes soiled with dirt and even blood. It was in 1980 that he began to draw with grease pencils on recovered flea media.

He made his first films in 8 mm from 1964 during his holidays in Greece or the Balearic Islands. Like Lionel Soukaz, he is one of the first French experimental filmmakers to address the theme of homosexuality (Le gant de l'autre, 1977). His practice will evolve towards a more formal exploration of the characteristics of cinema: luminous calligraphies (Gestuel, 1978), grain of the film (Le grain de la peau, 1986); either to direct cinema (Monsieur Loulou, 1980). These research finds their paroxysm in Capitale-paysage (1982-83), mixing snatches of conversations, work of concrete sound and rhythm, and kaleidoscopic effects.

Capitale-paysage

Michel Nedjar

"In this swirling and colorful hymn to Paris, a kind of new Symphony - but jazzed up - of a big city, we find the almost ethnological attention to others, the work of concrete sound. In just over an hour, condensing almost a year of filming in Paris, we get the impression of a single day of sunshine, a continuous kaleidoscope in the most diverse city in the world. The novelty is the attention to detail, which earned us, right in the middle of a series of sweeps, capsizes, Mathieu-style calligraphy, veritable little Gnoli-style paintings: a woman's shoe, a sweater button, or still lifes, in the cubist way, graphic elements: such and such of the thousand and prescriptions that populate the streets. This film thus takes its place at the forefront of all thosewho celebrate the capital today. Weaving together so many "energies", making the disparate elements communicate, it is the most complete, the most beautiful of Michel Nedjar's filmic works." - Dominique Nogues.

Capitale-paysage

Cristaux

Teo Hernández

Michel Nedjar, Gaël Badaud

The tetralogy pieces are dominated by the concept and presence of death, foreclosure, fetal vertigo. As such, CRISTAUX is a real descent into an inner labyrinth, which we do not know if it is organic or cultural. At the same time, the film contains a dialectical break that initiates other semantic directions in Hernandez's work. Under the influence of Michel NEDJAR, the filmmaker abandons his traditional method of editing based on rushes. The operation is now completed inside the camera, filming. This more flexible way of proceeding ("the camera must become a second eye") is already reflected in the clear openings of Lacrima Christi: the Christian myth seems to be on the way to exorcising. The pantheistic intoxication - close to that evoked by Nietzsche - seizes places, objects and participants.

Cristaux

Gestuel

Michel Nedjar

Gaël Badaud

This film is the most "plastic", the most "actionist" of Nedjar: it is his In contextus or his Double Labyrinth. Except that here - a single actor filmed in close-up on a plain black background. Nedjar "wiggles" his camera, with Gaël Badaud manipulating a green net or a mirror, wearing a gas mask or covering his head with a red-skinned knit like a bloody balaclava, he inaugurates a search for luminous calligraphies that will soon be shared with Teo Hernandez.-- Dominique Noguez.

Gestuel

Lacrima Christi

Teo Hernández

Jakobois, Gaël Badaud

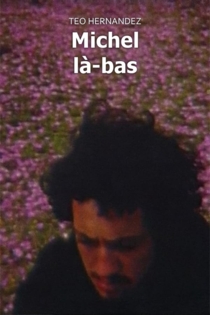

Lacrima Christi is the longest of the over 150 films made by the Mexican filmmaker resident in Paris, Teo Hernández. Part three of a tetralogy devoted to Christ’s Passion, Lacrima Christi is an exploration of the transfer between desire and myth that takes as its starting point a series of objects found in the flea market of Belleville.

Lacrima Christi

Cristo

Teo Hernández

Gaël Badaud, Armando Galvis

All of history, that of Christ or any other, permeates the world, leaves its mark, modifying and informing history, and all that the human reproduces and creates. The best way for historical interpretation or literary adaptation is to move as far as possible from literal interpretation. That is, it is a contemporary and personal interpretation. The story of Christ is an archetypal story. It has modified and informed a morality and a vision of the human being in the West, it must be taken for what it is and what it has become: matter.

Cristo