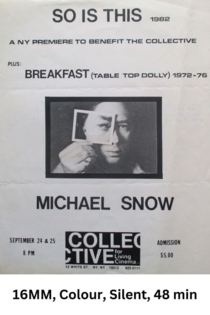

Michael Snow

1929 (96 лет)While Snow early established himself as a successful painter and musician in his native Toronto, it was his 1962 move to New York City that marked the beginning of his rise to international prominence. He entered into a long-lasting and fruitful dialogue with downtown Manhattan's artistic avant garde, exchanging ideas with figures such as Yvonne Rainer, Philip Glass, Sol LeWitt, and Richard Foreman, and developing of some of his most ambitious and influential works to date. His 1964 film New York Eye and Ear Control documents his growing involvement with the burgeoning free jazz movement, and the soundtrack boasts a lineup that includes Albert Ayler, Don Cherry, and Sonny Murray. Snow would continue to pursue improvised music, both on his own and in ensembles such as Toronto's CCMC. The generation and reception of sound in the broader sense emerged as one of his main concerns, reflected in performance and tape works that share qualities with contemporaneous experiments by composers like Steve Reich.

At the same time, Snow made alliances within the underground film scene centered around Jonas Mekas' Filmmakers' Cinematheque, an experience that encouraged him to find ways to transfer his concerns with music and photography into the realm of the moving image. He assisted Hollis Frampton on films such as Nostalgia(1971), and it was legendary director Ken Jacobs whose loan of equipment helped Snow create his most famous and influential work, the groundbreaking 1967 film Wavelength. Wavelength, which notoriously includes a 45-minute camera zoom within a fixed frame, remains one of the most studied and admired works of structuralist filmmaking. Other of Snow's films of this period, including Back and Forth (1969) and La Région Centrale (1971) similarly explored the mechanics of filmmaking to simultaneously investigate the functional processes of cinema and of thinking itself.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Snow, responding to a growing institutional commitment to his work, experimented more with large-scale installations, including public sculptures such as Flightstop (1979) and The Audience (1988-89). In recent years, he has focused on the specific nature and potential of digital media, yielding works like the video-film *Corpus Callosum (2002). Regardless of artistic genre, Snow consistently engages in an analytical discourse on the nature of consciousness and experience, language and temporality.

Two Sides to Every Story

Michael Snow

Two 16mm films are projected in a loop on a thin painted aluminum screen hanging in the middle of a room. We can hear the projectors at each end of the room, which project images on the central screen. We can see the same scene on each side of the screen: a woman, seen from the front and front back depending on the side of the screen, painting it with spray paint. A man then tears up the screen and goes through it, followed by the woman. We can see Michael Snow sitting further away, giving instructions to the woman. We can also see the cameras filming the scene from each side. Visitors in the room can walk around the screen and thus watch the scene from one angle or another. Both films are projected in synchronicity on the two sides of the screen.

Two Sides to Every Story

I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art

William D. MacGillivray

Dara Birnbaum, Michael Snow

This is an interesting little documentary about the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, which was apparently one of the global hotbeds of experimental/avant garde art- particularly video art- back in the 70's & 80's. MacGillvary interviews a number of the artists that were formative to the program. Many of whom would go on to become teachers at the school.

I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art

Toronto Jazz

Don Owen

Lenny Breau, Don Francks

Toronto is regarded as the third largest jazz centre in North America. This film features a cross-section of jazz bands of that city: the Lenny Breau Trio, the Don Thompson Quintet and the Alf Jones Quartet. Their styles show creative self-expression, hard work, and improvisation.

Toronto Jazz

Grand Opera: An Historical Romance

James Benning

Hollis Frampton, Owen Land

Grand Opera marks a stock-taking of Benning's work and his life, presenting a personal and artistic autobiography woven together with a series of events dealing with the historical development of the number pi, Benning's travels, and homages to Michael Snow, Hollis Frampton, George Landow (Owen Land), and Yvonne Rainer.

Grand Opera: An Historical Romance

Free Radicals: A History of Experimental Film

Pip Chodorov

Pip Chodorov, Stan Brakhage

Experimental filmmaker Pip Chodorov traces the course of experimental film in America, taking the very personal point of view of someone who grew up as part of the experimental film community.

Free Radicals: A History of Experimental Film

Seated Figures

Michael Snow

Although Seated Figures is characteristically confined by a specific placement of the camera — in this case, fixed to the rear of a pickup truck and aimed at the ground — the result is one of Snow's most visually compelling films. As Snow drives the truck over all kinds of terrain — he has offhandedly described the film as a "history of roads" — we see a variety of textures flowing in front of the camera as this road movie unfolds: asphalt, gravel, dirt roads, sand, grass, flowers and shallow creeks. The imagery moves between abstraction and representation as different travelling speeds affect the legibility of the visuals, and as manmade surfaces give way to the beautifully variegated patterning of nature.

Seated Figures

To Lavoisier, Who Died in the Reign of Terror

Michael Snow

To Lavoisier Who Died in the Reign of Terror (1991) is a collaboration with filmmaker Carl Brown, who specializes in homebrewed chemical film development. In a series of tableaux, people perform everyday tasks — sleeping, dining, reading, card-playing — as the camera arcs past and over them (the replete set of positions recalls La région centrale’s movements). Brown abraded the film stock, creating a continuous dynamic surface-effect tension with the comparatively static views and cueing the soundtrack, the crackle of fire. The physics and chemistry of combustion were the scientific focus of Lavoisier, the 18th-century savant.

To Lavoisier, Who Died in the Reign of Terror

‘Rameau’s Nephew’ by Diderot (Thanx to Dennis Young) by Wilma Schoen

Michael Snow

Kevin Wenzel, Munro Ferguson

Described (rather cheekily) by director Michael Snow as a musical comedy, this deft probing of sound/image relationships is one of his wittiest, most entertaining and philosophically stimulating films. In his words, the film “derives its form and the nature of its possible effects from its being built from the inside, as it were, with the actual units of such a film, i.e. the frame and the recorded syllable. Thus its ‘dramatic’ element derives not only from a representation of what may involve us generally in life but from considerations of the nature of recorded speech in relation to moving light-images of people.’”

‘Rameau’s Nephew’ by Diderot (Thanx to Dennis Young) by Wilma Schoen

Presents

Michael Snow

The apparent vertical scratch in celluloid that opens Presents literally opens into a film within the film. When its figure awakens into a woman in a 'real' unreal set, the slapstick satire of structural film begins. It is not the camera that moves, but the whole set, in this first of three material 'investigations' of camera movement. In the second, the camera literally invades the set; a plexiglass sheet in front of the dolly crushes everything in its sight as it zooms through space. Finally, this monster of formalism pushes through the wall of the set and the film cuts to a series of rapidly edited shots as the camera zigzags over lines of force and moving fields of vision in an approximation of the eye in nature. Snow pushes us into acceptance of present moments of vision, but the single drum beat that coincides with each edit in this elegaic section announces each moment of life's irreversible disappearance.

Presents